Anthony Mays

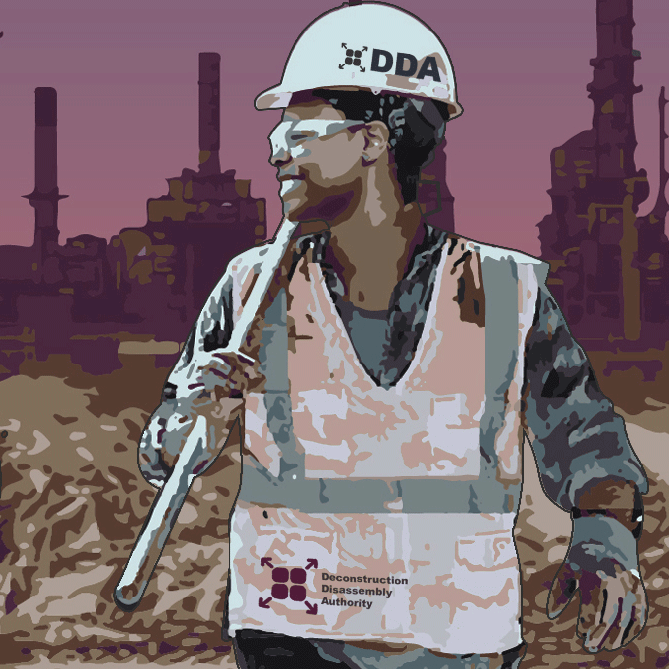

St. James Parish, LA | Disassembly Operator, Deconstruction and Decommission Authority

2035

Anthony Mays is a Disassembly Operator, Deconstruction and Decommission Authority and formerly incarcerated African-American man from St. James Parish. Louisiana has one of the highest per capita incarceration rates, a modern rendition of the state’s slave-based economy. Thanks to the Green New Deal jobs guarantee, Anthony enrolls in a series of career training programs preparing him for a role with a new Delta Regional Authority Department while he is in prison. In addition to the training, Anthony is able to quickly transition to a quality job after he is released and his employer pays for him to finish his Associates degree. He appreciates the Green New Deal’s focus on providing quality jobs and the impact this has had on his family and friends, as well as in his own life. This takes place in 2035.

Interviewer: Anthony, thank you for joining me today. I’m excited to speak with about a few different topics related to how the Green New Deal has impacted your life. Sound good?

Anthony Mays: Yup, ready to begin to whenever you are.

Interviewer: Alright, so let’s start with you telling me a bit about what you were doing prior to your role as the Disassembly Manager at the Bayou Bridge Pipeline.

Anthony Mays: I thought it sounded interesting, but I was still a bit skeptical. Some of the older workforce development programs I’d heard about seem to talk a good game but couldn’t really guarantee you a good job at the end of the day. So DDA was really different from the typical organizations I’d come across and the jobs they had listed all had good salaries. That was the main draw, but the more I learned about the Green New Deal and what it meant for St. James the more I began to recognize that this was something I didn’t want to pass up. I really appreciate my job...I have a pretty good salary while giving back to my hometown. I’m still surprised at how it all worked out given how most folks with a record never hear back from the jobs they apply to.

Interviewer: The national decarceration movement has yielded many victories for those pushing a new vision for criminal justice and policing.

Anthony Mays: Definitely, this has been a blessing. Prior to serving time I was in classes to earn an Industrial Maintenance Associate’s at Delgado Community College but never finished… a neighbor of my parents did time when I was younger and from their experience I figured, after having a criminal a record, it was going to be impossible to find a job that lined up with original plans. The DDA helped me do that, even paying for me finish my degree and complete an EPA hazardous waste certification.

Interviewer: That’s great to hear, congratulations on completing your studies. Can you tell me about your process to becoming a Disassembly Manager?

"... I really didn’t know much about energy system management prior to my experience with the DDA, but as it turns out, the Industrial Maintenance degree I was working towards was a great fit for the Disassembly Operator role. ...”

Anthony Mays: I remember when I applied for the position, it was a really easy process to sign up for the GND jobs database, find a position, and apply just from my cellphone. This may seem like a small thing, but I’ve applied to jobs in the past and sometimes they just weren’t made for phones and I would spend so much time just trying to hit send.

Like I said earlier, when I saw the position, it was a huge upgrade from anything I thought I could get, so I applied for the apprenticeship program right away. I was an apprentice for six months – with the same pay – and then became a full-fledged employee. I really didn’t know much about the energy system management prior to my experience with the DDA, but as it turns out, the Industrial Maintenance degree I was working towards was a great fit for the Disassembly Operator role. So, after a couple of years of working and studying, I became a Disassembly Operator on the Bayou Bridge Pipeline.

Anthony Mays with the Bayou Bridge Pipeline.

Many of these pipelines and other infrastructure need to be taken down to avoid further polluting communities and wildlife with the increasing changes from climate change. I’ve noticed more people have been leaving their homes down here to move north as part of the Migration Support program. Even if the people are gone, there is all this infrastructure that is left and will be destroyed if we don’t proactively disassemble it.

In a few more years, I hope to be a Co-Manager for the Convent facility in the Parish. That’s a huge site, but I think I’ll be ready. You know, it’s crazy. I remember when I first learned that this was site shutting down and hundreds of people lost their jobs back in 2020. That was a wild year...

Interviewer: Let’s not go back to 2020 please . Sounds like you’ve found a great role for yourself, can you talk a little bit about what your day-to-day looks like?

Anthony Mays: Sure, right now we’re taking apart a 100-mile section of the pipeline. I coordinate with a team of 5 other Operators to manage the deconstruction of hydraulic systemics, hoses, valves, and electrical devices. Most days we spend a couple hours out at the site and a couple more in the office coordinating the storage and reuse of the deconstructed elements of the system. There’s a good, respectful culture here and I really enjoy working with everyone on my team.

One thing, before I forget - I didn’t hear these stories until recently, but people fought against the pipeline so hard when it was being built back in the 2010s. Tribal leaders and some local activists even set up a camp called L’Eau est la Vie out in the bayou to try and stop construction. Some of the folks who founded it came by the other day to talk to us about the farm they set up on the old camp site. It’s makes me happy to think about how much different work is being to repair the whole length of this pipeline. Our site here is just one part of that.

One last thing about my job, unlike former jobs at the chemical plants or refineries, this one is much safer due to new regulations and I have great health benefits. In fact, we’re advised to take quarterly doctor visits just to make sure we’re all good. The new health clinic in St. James has made a huge difference. It’s convenient for me and the other folks employed at the DDA, but I know a lot of the other town residents are really proud of having won the battle to have affordable quality health care right here in town that serves all the locals too.

Interviewer: Amazing, can you talk a little about what this job means to you personally?

Anthony Mays: I mean, first of all, I’m making enough money to take care of myself, I have job security, my health insurance is covered by the American Wellness Act, I can enjoy my paid time off, and support my family while treating them every now and then. Another thing I think about is how growing up, I knew a lot people that were sick and even died after spending decades living near the Dyno Nobel chemical plant over in St. James. I know plenty of people that have died from cancer, have to live with asthma, experienced problems with their pregnancy. It’s terrible what they were allowed to do to us. But it feels good to take the pipeline down and know that it’s going to be replaced with something that doesn’t cause physical harm to the people closest to it, just like what happened with the petrochemical plants that came down a couple years ago.

For instance, the section I'm working on now goes through this huge field that I’ve heard can be flooded and turned back into a marsh where the fishing and oystering will be good. They say this whole area is going to be underwater in a couple decades, but in the meantime the Infrastructure Decommission and Reuse (IDAR) program is planning to remediate the grounds and allow for public recreation as a temporary extension of the Mississippi River Trail. Regardless of what it becomes, it’ll be better than the pipeline.

Interviewer: The oil industry, despite the harm they cause your community, was supported by some citizens and politicians because of the jobs they created. Now that we’re five years out from the government imposing strict decarbonization regulations, and have organizations like the DDA up-and-running, how has the job market been impacted in the communities here?

Anthony Mays: For one thing, big oil isn’t that big anymore. They’re decreasing the amount of people working at these places on the Chemical Corridor and almost nowhere is hiring. Financially, I think most people are better off though, even with those layoffs. I’ve heard from friends that a lot of employees at the remaining plants are leaving because the pay and benefits are just as good with the DDA and other government agencies, plus the work is safer and more stable here, like I said before. The Green New Deal created thousands of new union jobs around here, and most people I know are able to find something decent. Not every job is amazing but no one’s just making $9.25 at the Dollar General either. I mean, even the chain stores even had to raise their pay since most people can find a GND-related job whether through the government or some other co-op related to it. I know a few people that have been installing solar panels for a minute now.

Interviewer:I’m so glad to hear that. Well, Anthony, I want to thank you again for the opportunity to hear from you.

Anthony Mays: I would just say to anyone out there listening that if you need a job, check out your local DDA site or another Green New Deal program. You should be good with them.